|

by Stephen Fox

Although it is not difficult to find underappreciated

or forgotten chamber music involving the clarinet, it is a rare privilege

to resurrect a major work from the dusty archives where it has lain neglected

for nearly a century. Such is the case with the Trio in D for clarinet,

cello and piano by John Ireland.

Ireland and the clarinet John Nicholson Ireland (born 1879 near Manchester; died 1962 in Sussex) is recognised now as one of the towering figures in British music in the first half of the 20th century. The promising start to his musical career - he entered the Royal College of Music as a student of piano and organ at the age of 14 - contrasted with the unhappiness that marked most of his long life; orphaned at an early age, he was plagued by self doubt and personal angst, and he never received the public acclaim which was accorded some of his colleagues. Ireland’s distinctive and highly varied musical style, which was intensely personal and imbued with the spirit of Romanticism, grew out of a rigorous grounding as a pupil of Stanford at the RCM, blended with the influence of Continental masters. He drew inspiration from literary sources (the fantasies of Arthur Machen and the Satyricon of Petronius, for example) and from his love of the English countryside, although unlike some of his contemporaries, he did not delve extensively into folksong for musical material. He is perhaps best known for his piano music and songs; and while he wrote a number of pieces for orchestra, he never attempted symphonies or operas. Ireland’s words “The clarinet is by far the finest wood[wind] instrument…” testify that - as with a number of other composers, to the gratification of those of us who play the instrument! - the clarinet was the wind instrument which he held in the highest regard. His limited body of chamber music is mostly for strings and piano, and includes only three works which involve winds, but all feature the clarinet: the Sextet for clarinet, horn and strings (1898), the Trio (1912-14), and the Fantasy-Sonata for clarinet and piano (1943). A seminal influence on the neophyte composer as a teenager was hearing a performance in London by Richard Mühlfeld of the Brahms Clarinet Quintet. His earliest compositions were heavily influenced by conservative European models, particularly Brahms (leading to the infamous comment by his teacher, C. V. Stanford, on Ireland's first creative attempts: “All Brahms and water, me boy, and more water than Brahms…”). Not surprisingly, then, the Sextet sounds for the most part like a blend of Brahms and Dvorák. Nevertheless it is a wonderful work, full of melodious geniality, and very much deserves to be better known. At the opposite end of Ireland’s career

stands the much better-known Fantasy-Sonata, which has been dubbed the

high point of his chamber music oeuvre (Stuart Craggs). Parallelling

the relationship of Brahms and Mühlfeld, Ireland was stimulated to

produce a clarinet sonata through close collaboration with a fine orchestral

and chamber clarinettist, in this case Frederick Thurston.

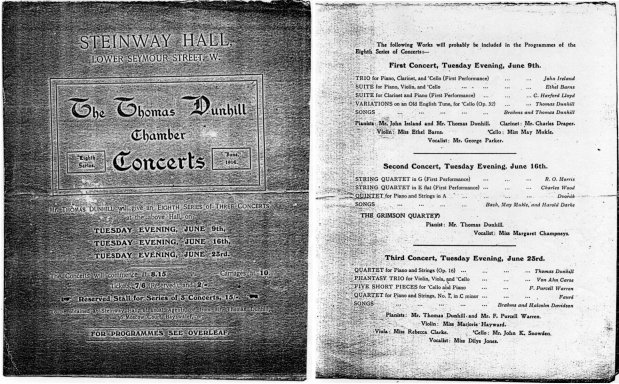

History of the Trio The exact impetus or inspiration for the composition of the Clarinet Trio - for example, whether it was written for and in consultation with a specific clarinettist - is unfortunately not recorded. The manuscript testifies that it was begun in April 1912 and finished in October 1913, and revised between then and February 1914. The Trio received at most two public performances, possibly only one, during Ireland’s lifetime. It is listed among works which “will probably be included” in one of the Thomas Dunhill Chamber Concerts at Steinway Hall in London, on June 9th, 1914, with Charles Draper (clarinet), May Mukle (cello) and the composer as the performers; the listing states that this would be the “first performance” of the piece. It also appears on the programme of one of Isidore de Lara’s War Emergency Concerts, also at Steinway Hall, on March 25th, 1915. Evidently dissatisfied, though for particular reasons which are now unknown, Ireland began shortly afterwards to rework the piece as a conventional piano trio, with violin instead of clarinet. Changes included transposition from D into E, discarding of the original slow movement (if present), and various alterations in the accompaniment, texture and subordinate themes. In this form it was shelved again. Finally, more than two decades later, material from the piece - radically altered, and with an entirely new slow movement - was used as a basis for Ireland’s Trio No. 3 in E for violin, cello and piano, which was completed in 1938. As with the Sextet, Ireland kept the Clarinet Trio, or at least those parts which he chose to preserve, stored away but unpublished for most of his life. Though he was finally persuaded to release the Sextet to the public in 1960, the Trio remained hidden. During 2002-03, the present writer assembled the surviving source material and produced a reconstruction which as far as possible approximates Ireland’s original version of the work, given the information now available. The revived Clarinet Trio was given its first performance by the writer's chamber group, the Riverdale Ensemble, in Toronto in June 2003. The same group was invited to present the work at the ICA ClarinetFest in College Park, MD, in July 2004. Further performances have allowed gradual polishing of the reconstruction and editing. The first U.K. performance is (at the time of writing) scheduled to be given by Alex South at Glasgow University in November 2007. The world premiere recording has been released by the Riverdale Ensemble (details are available elsewhere on this site). Publication of the Trio has been undertaken by June Emerson Wind Music in the U.K., from whom the printed music is now available (see below for further information). The process of reviving the Clarinet Trio

has been carried out with the approval of the John Ireland Trust.

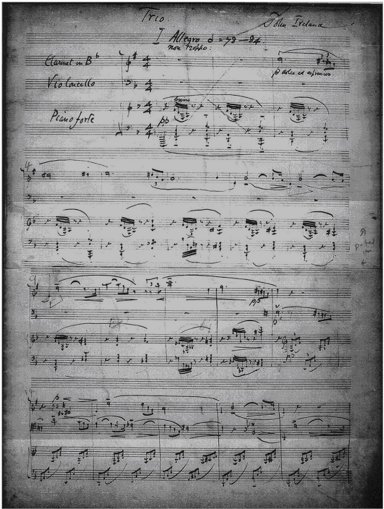

Source material On Ireland’s death his manuscripts were willed to Norah Kirby, his secretary and housekeeper, who in turn donated them to the British Library in London. They were sorted and arranged by the musicologist Ernest Chapman, and the volume containing the surviving parts of the Clarinet Trio (British Library catalogue number MS 52887) was bound in 1985. Very unfortunately, the manuscript is incomplete

(whether due to accidental loss, or to Ireland’s deliberate destruction

of parts he deemed unworkable, is not known; a combination of both is likely).

The volume contains the following parts of the original Trio-

The original clarinet and cello parts have disappeared; there is a vague hope that they might survive in music collections left by Charles Draper and May Mukle, but enquiries in that direction have so far led to nothing. Essential collateral information is also provided by the Piano Trio No. 3, published by Boosey & Hawkes. A copy of the programme for the planned premiere performance in 1914 is held by the John Ireland Trust. The work is discussed at some length (albeit

primarily in reference to the Piano Trio No. 3 rather than as an independent

work) in Fiona Richards' The Music of John Ireland (Ashgate, 2000).

It is also listed in Stewart Craggs' John Ireland: a Catalogue, Discography

and Bibliography (Oxford, 1993). Though the citations in these books

are valuable, they are incomplete and somewhat inconsistent: Craggs

seems not to have noticed that the manuscript includes some material from

the interim violin version; the authors disagree on the date and venue

of the first performance (Craggs follows the 1914 concert programme while

Richards gives the 1915 date, with neither mentioning the other); and both

books state that the piece is for “clarinet in Bb”, even though the manuscript

specifies clarinet in A for the final movement.

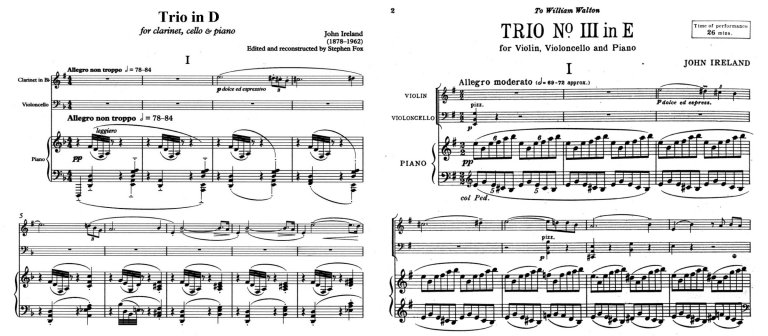

First movement The manuscript preserves the first movement intact (pp. 1-16) except for a few bars on the last page, which is missing. The score is largely unambiguous, so the principal challenge is to decipher questionable notes (resulting from sloppy writing and ink blots) and numerous editorial instructions of varying legibility. These annotations were added at various times - during editing of the first version, during the adaptation to the first violin version, and during the composition of the 1938 Trio - so it is often not totally clear which ones are to be followed for the present purpose. The missing part at the end of the movement, deduced to be five bars long, has been restored by close analogy with corresponding material in the 1938 Trio: the last four bars were transferred verbatim (except for transposition), leaving only one transitional bar to be reconstructed. Rebuilding this bar was not difficult, given the necessity to preserve the melody line, the harmonic progression and the rhythmic pattern established in the previous bar. The extent and type of the changes that took place between the original Clarinet Trio and the 1938 Piano Trio can be assessed by comparing the opening material from each:

From these examples, the evolution of the music is apparent in two principal ways. Firstly, the original piano accompaniment, which has a halting feel and a rather sparse texture, was replaced by a continuously undulating movement (which is very typical of Ireland's piano writing). Secondly, the triplet figure in the melody line has been expanded from eighth notes to quarter notes, which alters the character of the tune fundamentally, replacing a slightly martial feel with more expansive lyricism. The secondary thematic and development material in this movement was replaced completely during the transformation to the 1938 Trio. This movement is written for clarinet in

Bb. However, one of the passages contains a bottom Eb, unplayable

on a standard clarinet. In the grand scheme this is not particularly

significant - another harmonically consistent note can be substituted -

but if one wishes to be completely accurate, this passage can be played

on clarinet in A. In fact, for technical convenience in other respects,

clarinet in A may be preferred especially for the end of the movement;

thus, the entire movement can profitably be performed on clarinet in A

instead of Bb, or a switch made from Bb to A partway through.

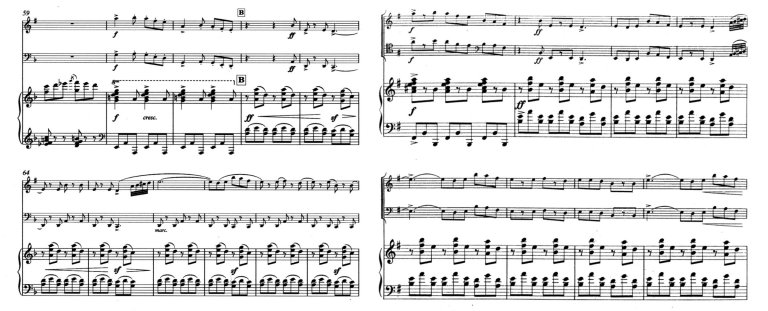

Scherzo This movement is represented by only two surviving manuscript pages (pp. 29-30). Though it is the second movement in the interim violin version and the 1938 Trio, the page number sequence thus indicates that it came third in the original version (see below). In spite of its incomplete state, reconstructing the Scherzo from the 1938 Trio - incorporating the two original pages at the appropriate point - was relatively straightforward and non-problematic. Comparison of the extant fragment with the corresponding section of the 1938 edition shows two general alterations: transposition from D minor to E minor; and transformation of the original constant 6/8 metre to irregularly alternating 6/8 and 9/8, which has been carried out by condensing the rhythm and dropping beats. Restoration of the original version thus requires, in addition to transposition, the expansion of each 9/8 bar into a pair of 6/8 bars:

When this process is carried out throughout the movement, the two surviving pages slot perfectly into place, giving us confidence that the reconstruction is a fair rendition of the original. Certainly, some details could be handled in alternate ways - the choice of which clarinet note to extract from violin multiple stops in the 1938 Trio, rectification of multiple stops in the cello part which are playable in E minor but not in D minor, whether to transpose a very high melody line in the violin part down to a more appropriate range for the clarinet, etc. - but these are minor matters which do not affect the architecture or the overall sound of the movement. This movement is scored for clarinet in

Bb.

The missing (slow?) movement After completion of the first movement

and reconstruction of the Scherzo, there is clearly a large gap in the

page number sequence in the manuscript (pp. 18-26, plus or minus a page

or two), demonstrating the existence of a second movement which is now

entirely missing and likely never to be recovered. It is reasonable

to surmise that this was a slow movement, but that is not absolutely definite,

and other than that we can say nothing about it.

Lento As mentioned above, the manuscript contains, in addition to the surviving parts of the Clarinet Trio, one section from the interim violin version. This is an introduction, marked Lento, to the last movement. The original clarinet version did not contain such an introduction (the last movement starts at the principal tempo, Con moto, immediately after the movement heading "IV"). It is possible that the musical material in the Lento was similar to that in the missing second movement (see above), but that is purely conjectural, and cannot be assumed. In the absence of any other slow movement, the decision has been taken to adapt the Lento and include it in the revived Clarinet Trio. Whether it belongs is debatable, given that there is no evidence that it ever existed for clarinet; performers are invited to make their own judgements about this. If nothing else, its inclusion preserves an interesting and distinctive piece of Ireland's writing which would otherwise be lost. Incorporation of the Lento requires it to be transposed down a whole tone, in parallel with the rest of the Trio - to preserve the attacca into the finale - and adaptation for the clarinet of violin-specific writing, such as tremolos and one passage with an extremely high tessitura. The transposition makes it necessary to move the opening and closing cello melody an octave higher than in the manuscript (which calls for scordatura, with the C string tuned down to B), and also puts the lowest notes in the piano part below the range of the normal piano. The Lento is currently written for clarinet

in Bb, though clarinet in A would be equally valid and convenient.

Final movement This movement is complete in the manuscript (pp. 38-50). Editing for performance thus requires only interpreting one somewhat ambiguous cut (resulting from a replacement page being inserted in the score), deciding how to handle a pencilled-in instruction to transpose one section, and some individual note concerns. While extensive structural and detail changes took place between the Clarinet Trio and the 1938 Trio, the first and second themes were preserved intact, though a third theme in the original - a chant-like tune - was later dropped. As mentioned above, the manuscript contains four pages of an unfinished, alternate version of this movement, also for clarinet, but with a different principal melody from that which appears in the Clarinet Trio and which was carried over in essence into the 1938 Trio. Possibly, then, it is a first draft, which Ireland preserved in case he wanted to return to his first melodic idea in later reworkings of the piece. Clarinet in A is specified for this movement.

Style and analytical comments By 1912 Ireland had found his voice as a composer, so those hearing the Trio for the first time would likely not be surprised to learn the identity of its creator. In its musical language it is worlds away from, say, the Sextet of only 14 years earlier. Where Continental musical influences are still apparent, it is most often Debussy, not German or Central European composers, whose shadow is cast over the Trio. Some parts - for instance, the second theme in the first movement (which reminds us of “Teddy Bears’ Picnic”!) - could not possibly be any nationality other than British. At times, though, Ireland's experimentation with compositional technique is apparent; the Lento, with its ambiguous piano harmonies over a cello ostinato, would not have been out of place in the work of a composer of several decades later. (The slow movement of the 1938 Piano Trio, in contrast, is melodic, sentimental and very much in the Romantic tradition.) Though the moods in the Trio are varied, there is a strong presence of the martial element that tended to pervade Ireland’s works written in wartime and in the years when war threatened. It is thus probably not a coincidence that the Trio, composed when the First World War was in the air, was released in a new form on the eve of the Second. We do not know why Ireland chose to drop

the clarinet in favour of the violin, but as has been pointed out, it was

definitely not a lack of esteem for the clarinet in general. Perhaps

some slight errors in handling the range of the clarinet, and the complaints

which may have resulted, played a part; there are several uncomfortably

high passages, involving prominent use of top A and G#, for example.

(A hint that these notes may have caused trouble is found in Ireland’s

letters mentioning the high notes in the Fantasy-Sonata, which were included

in close consultation with Thurston but still caused Ireland considerable

anguish.)

The printed music As mentioned, June Emerson Wind Music has undertaken the task of publishing the revived Clarinet Trio, for which we are very grateful. Given the partially reconstructed nature of the Trio, the original hope had been to produce an Urtext-style publication, with copious footnotes and all the details of the editing visible. Since this is not the policy of Emerson, however, the decision was taken to release a traditional performing edition, with the general process of the reconstruction explained in the preface. Sensible editorial decisions have been made regarding ambiguities and clearly evident wrong notes in the manuscript, and to achieve consistency in articulation, phrasing, dynamics and pedalling. In order to deal with the bottom Eb in the first movement and to provide flexibility for the performer in general (as discussed earlier), it was also originally envisaged to print the whole first movement for A clarinet as well as for Bb clarinet. This did not materialise, though the movement does contain an ossia line for clarinet in A for the one section which includes the Eb. A list of specific editorial details is

in preparation, and will be posted below shortly.

Conclusion Resurrecting a piece of music in this way raises the question of the fairness or morality of bringing to light a work previously suppressed as unworthy or unfinished by its creator. With a long-deceased composer, one would have no hesitation in doing so; any newly discovered morsel of music, however modest or unfulfilled, by one of the "great masters" would unquestionably be eagerly received and published. Being riven with self-doubt, Ireland was ruthlessly critical of his own work, and it was not unusual for him to revise extensively even compositions which had already been published; works he considered irretrievably bad were simply destroyed. Thus it would be a mistake to reject the Clarinet Trio solely on the basis of his testimony, written in 1943, that “…The musical material & the emotional content were all present in the original version, but badly expressed & clumsily managed.” Comparison with the 1938 Piano Trio provides a frame of reference for assessing the quality of the Clarinet Trio. Overall the later incarnation shows more polish and the benefit of 25 years of composing experience. The opening of the first movement feels more comfortable with the later undulating piano accompaniment than with the halting pattern first used; and the development section of the original first movement unquestionably contains some weak spots. It is not clear, however, that the new thematic material incorporated in the 1938 Trio is necessarily superior to that in the earlier work. It can be emphatically stated that although the Clarinet Trio is recognisably related to the Piano Trio No. 3, the differences are sufficient to give the two works their own separate identities; it would be quite incorrect to view either as simply a transcription or a draft of the other. Doubts may be expressed about the authenticity of the resurrected Clarinet Trio, given the incomplete manuscript and the amount of reconstruction necessary to produce a performing edition. For the record: 72% (599 out of 832 bars) of the piece survives in the manuscript; and 95% (789 out of 832 bars, i.e., all except the Lento, which may be omitted in performance) can be confidently stated to be at least a close approximation of the original. Each reader must make his or her own determination of the legitimacy of the final result. As a precedent, there is one other example of a work of Ireland’s - the piano solo Ballade of London Nights - which he never finished, and which was completed (by Alan Rowlands) and published after Ireland's death. Ultimately, the John Ireland Trust is the guardian of the best interests of Ireland and his memory, and their judgement as to the suitability of releasing the Trio is to be respected. The Trio in D is a major work with considerable

musical interest and appeal for the listener, and it has been worth the

time and effort required to bring it back into the public eye. As

the only piece for this standard instrumental combination to be found in

the rich and distinctive genre of British late Romantic music, it should

become a significant addition to the repertoire.

Acknowledgements Thanks are due to all those who have assisted

in this project: Dr. Richard Faria of Ithaca College for providing

the initial impetus; the Trustees of the John Ireland Trust, notably Bruce

Phillips and the late Peter Taylor, for releasing the score, providing

other valuable information and for giving their approval for publication;

Alan Rowlands for his thoughtful suggestions and time spent examining the

score; June Emerson for agreeing to publish the Trio and Rachel Emerson

for handling the transcription and printing; Jeanne Roberts for typesetting

the music and suffering though many rounds of editing; Russell Denwood

for editorial assistance; Pamela Weston for her encouragement and for facilitating

contact with the publisher; Marguerite Baker for including a performance

on the crowded schedule for ClarinetFest 2004; cellists Laura Jones and

Helena Likwornik for their patience in turning barely-legible handwriting

into music; pianist Ellen Meyer for countless hours spent deciphering and

interpreting the barely-legible manuscript score and collaboration throughout

the process; and many others who have offered enthusiastic moral support.

First page of manuscript of Clarinet Trio

|